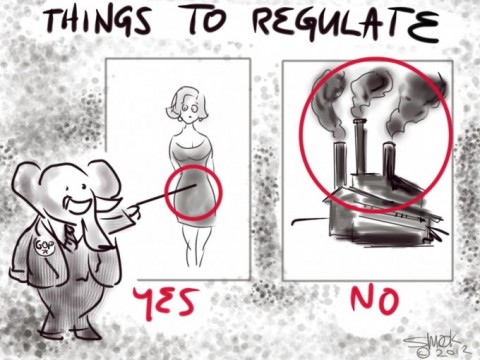

On my last post, I discussed some instances of corporate malfeasance. One of the readers commented, that “if a corporation breaks the trust, suspend it for a decade. Liquidate assets to payout non involved employees.” I don’t think this is the right way to punish corporations, but the general sentiment—putting the consequences of illegal activity on those responsible—is correct, and the question itself is an interesting one. Thus, I’ll discuss how I’d go about punishing corporations for illegal activity.

The Corporate Structure To discuss punishing companies, you have understand the corporate structure. I’d consider the people associated with the typical large corporation to be in four main roles.

Shareholders: Shareholders own the company, but usually don’t have any direct say in the management or operations of the company.

The Board of Directors: The board of directors—elected by the shareholders, but almost always individuals recommended by the executives—direct the company, design the high-level strategy, and are ultimately responsible for all the actions of the company.

The Executives: The ‘C’-level executives (e.g. CEO, President, CFO) are responsible for managing the company and implementing the directions of the board. In practice, they tend to be as least as strategy-focussed as the board, and likely guide the board as much as the board guides them.

The workers: These are all the people who work for the company but aren’t actually part of the executive team.

Of course, these positions aren’t mutually exclusive. Almost always, the CEO is also a shareholder and a member of the board.

How punishment works today

So, let’s look at the 2007-2008 banking crisis that nearly destroyed the world’s economy, driving millions of people out of work. It happened because banks gave loans to people who couldn’t actually afford the loans, packaged them together, and fraudulently claimed that the loans and package as a whole were higher quality than they actually were. Then they paid the rating agencies to agree, so they could sell those bad loans to investors who had no clue what sort of crap they were buying.

Thus, if you look at who was responsible for this crisis, you should give credit to both the workers who misrepresented the loans and the executives and board who were encouraging this fraudulent activity because it grew the company and increased their bonuses.

Seeing this malfeasance from these individuals, the SEC’s response was to allow the board, executives and workers to keep their fraudulently-accumulated wealth, and punish the shareholders by fining the companies large amounts of money (for the biggest players, tens of billions of dollars). Thus, the people in the corporate organization who were most responsible were rewarded, and the people least responsible were punished.

Suspending the corporation

Let’s go back to the idea of suspending the corporation and paying out assets to the non-involved employees. I see a few problems with this approach. First, most of the value of big corporations isn’t in their assets. For instance, Coke (NYSE: KO) has an enterprise value of $217 billion—that’s what the market thinks the company is worth. But they only have assets of $25 billion.

The difference is because Coke as an operating company is worth far more than its assets. Think about it. Would you rather have a bunch of trucks, a big mound of sugar, and a few factories and warehouses, or would you rather have distribution agreements with millions of stores and restaurants, a brand that almost everyone on earth recognizes, and the recipe for a semi-addictive product that people constantly purchase? Thus, if we suspend the company and distribute its assets, we’re destroying most of the value of the corporation.

Second, this approach, too, would mostly punish shareholders rather than the people responsible—the board and executives. The shareholders would lose everything, the board and execs would keep their ill-gotten wealth.

Third, shutting down massive corporations would leave a huge hole in the economy and would be politically controversial. For politicians to be willing to do this, the corporation would have to be loathed. Otherwise, politician’s own incentives would make them unwilling to take such drastic action. Thus, suspension might exist as an ultimate punishment, but in practice would never actually be used.

My solution

Instead, I’d like to punish the “corporation” by throwing the people responsible in jail and clawing back their illegally obtained wealth. As such, I think top level executives and board members should almost always be held responsible for major violations by their companies, regardless of whether or not it can be proven that they “knew”. Their job is to know, and—for major violations—it seems likely to me that almost always the executive would know (or have deliberately created a culture that encouraged violations). The punishments should typically involve both significant jail time and fines equal to or greater than to the ill-acquired wealth.

On top of this, I’d make director’s insurance (which pays for lawsuits against board members), illegal. In effect, director’s insurance moves the costs of a director’s illegal activity from the director to the shareholders. I’d consider products that transfer the costs for illegal activity from the guilty to the innocent to have negative value to society.

This approach would certainly make it riskier being a top executive, but that could become part of the reason why CEOs are paid 350 times what the average worker is. Plus, if a particular issue could get a CEO thrown in jail, I suspect that CEO will pay much more attention to that issue than they would otherwise. If, as a result, corporations care less about money and more about being squeaky clean, it will lower profits, but likely result in a better world.

The challenge

The biggest challenge with this approach is that it has to be based on law. If we use a vague standard like “breaks the trust”, we’ll end up with politicians’ enemies in jail, and politicians’ donors doing whatever the heck they want. So, we need the prosecution of corporate offenders based on law, to at least give us a fighting chance of going after people that the politicians like.

One problem, however, is that you can’t encode good behavior in law. Take Nestlé. In third-world countries, they contributed free formula to new mothers in hospitals. Mothers who accepted the formula would stop lactating and were forced to continue buying it when they returned home, hurting both babies and parents. Nevertheless, regardless of how unethical this strategy is, it’s hard to think of a law that could be created to prevent it. (Are you really going to stop corporations from donating goods to helping children in hospitals?)

The bottom line

Maybe in the long term, we could create a “don’t be an jerk” law, which would be considered broken if 95% of the population polled think someone’s being a jerk. Implementing that sort of law is feasible with online voting, but it isn’t likely to be seriously considered (not the least because, if it did exist, the first people to break it would probably be politicians, the guys who make the laws). Thus, I think the combination of reasonable corporate laws, easier standards to prove the culpability of executives in their company’s malfeasance, and jail time and fines is the best way to deal with corporate crime today.