The next British Columbia provincial election is happening in May. This election is particularly interesting for me because one of my friends, Jonina Campbell, is the Green Party’s candidate to be the MLA for New Westminster. On Saturday, I attended a dinner/fundraiser she put on. It was the first time I’ve attended a political event in the 20 years, and I was impressed.

My connection to Jonina

I first met Jonina in 1998 when I joined her ultimate team, Apocalypse Cow. That team played a lot of ultimate, but did just as much socializing. Something like five marriages resulted from that team, including mine.

Members of Apocalypse Cow even tended to live in similar areas. At one point, Jonina and her husband actually lived in the same apartment building as us. In a way, our lifestyle was sort of like Friends, but with a larger, less sexy cast, fewer coffee shops, and a geekier vibe.

We used to visit Jonina and her husband every Wednesday night to watch The West Wing, probably my favorite American TV show. When the World Trade Center fell, I saw it from Jonina’s living room and heard Jonina’s horrified gasp. My wife actually went into labour at Jonina’s house the night before my son was born.

Will Jonina be a good MLA?

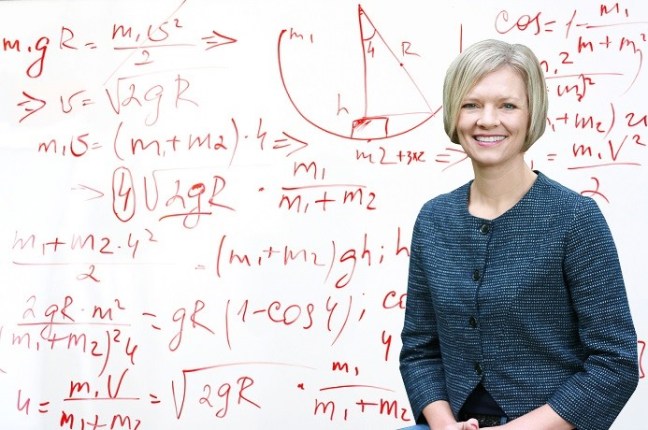

Thus, I know Jonina fairly well. She’s bright and thoughtful, but almost ridiculously extroverted and charming. She has integrity—she’s clearly not in politics for her own ego or enrichment, but rather because she wants to effect positive change in the world. She has empathy and compassion, but is grounded enough to make the hard decisions when necessary. And she’s insanely energetic.

When I think about the people I know well, there’s actually many I wouldn’t vote for simply because they wouldn’t be that good at the job, would have terrible ideas, or would be in politics for the wrong reasons.

But I consider Jonina to be an ideal MLA. Her combination of honesty, brains, compassion, and energy is really rare, and I think it will result in her being extremely effective as an MLA. It’s fascinating listening to her perspectives on education, formed based on her experiences as a parent, a teacher, and the Chair of the New Westminster school board.

“The chance to vote for someone.”

That said, I was initially skeptical when I found out she was running for the Green Party, simply because I think BC will benefit from Jonina sitting as an MLA, but—in its entire history—the Green Party has only won one seat in the Legislature. So, running as a Green Party candidate seemed like a hard path to becoming an MLA.

But the fundraiser this weekend convinced me, for several reasons. Andrew Weaver, the party leader spoke, and he raised a very good point—the Greens actually give the electorate the chance to vote for someone, rather than against someone.

This simple statement resonated with me, because I feel like provincially, my entire adult life, I have been voting against parties. Christy Clark’s Liberals are actually conservatives. To me, they seem to be corrupt, pandering to their biggest donors, real estate developers. They don’t seem to care about public education and are actually underfunding schools to the extent that students take days off because the government isn’t providing enough money to keep the schools open. They don’t seem to care about sustainability or the long term future of BC, but rather making money for their friends. They only started pretending to care about affordable housing when it became the issue most important to voters, ahead of even the economy. So, I’m not a fan of the Liberals.

What about the other guys?

Thus, the NDP has frequently been my “not the Liberals” choice, but only because they seem to be the lesser of two evils. In the last election, they didn’t focus on communicating their plans. Instead, they said “we’re not the Liberals” so much that I’m pretty sure they were considering changing their name to the NTL. That’s not to say there isn’t something to that argument. They might not fund public education, but at least they wouldn’t view it the way Clark seems to, as nothing but a cost center. They probably wouldn’t put real estate developers ahead of their constituents to the extent that the Liberals do. But voting for the NTL party is distasteful.

What’s more, the NDP seem as beholden to their union donors as the Liberals are to their real estate developers. I’m not only scared of the NDP crashing the economy but also making extreme pro-business decisions to reassure people who are concerned about them crashing the economy. (In fact, in this respect, I think the NDP has an insurmountable brand problem.) So, maybe I’d vote for the NDP, but not because they convinced me that they were the right party to lead.

The appeal of the Greens

The Green Party, in contrast, seems far less ideologically-based than either the Liberals or NDP. I expected it to be the party of hippies, but it seems to actually be the party of evidence-based reasoning. Weaver is a climatologist and several of the party’s candidates have Ph.Ds, and the crowd at the event seemed bright and thoughtful. I had conversations at my table about sustainable logging practices, the statistical analysis of demographic data, the tech environment in BC versus Silicon Valley, and the long-term consequences of self-driving cars.

If you look at the Green Party’s policies, you’ll see that they’re focused not on what ideology demands, but what actually works—what the evidence suggests results in happy people and successful societies. Thus, they’re looking at community building, preventative medicine, education, integrated healthcare, and pushing decision making down into communities. Sure, there is some ideological stuff (e.g. opposing trophy hunting), but mostly the Green Party seems to be about practical evidence-based solutions that work over the long term.

My bottom line

Thus, Andrew Weaver is right—the Green Party is a party that you can actually get excited about. Politics has been becoming increasingly polarized, with people fighting about whether our society should be based on left or right ideology. In contrast, the Green Party seems to be saying, “Who care’s whether something is left or right? The only questions that matter are does it work, and is it sustainable?”

To me, that’s a refreshing change. It cuts to the heart of the issue, and provides an alternative to the horrible “if you like it, I must oppose it” war that politics is mired in today.