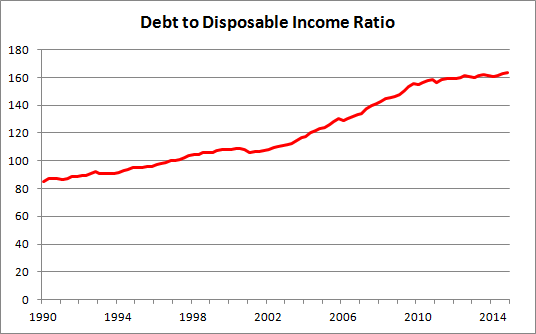

Income disparity has never been so high, and the Occupy Wall Street and other rallies around North America–while largely unsuccessful–show that people are starting to care. Even so, without some sort of intervention, these disparities are likely to increase.

Success often breeds success, for two reasons. First, people sometimes are successful not because of luck, but because they are more skilled. Where this is the case, you’d expect this skill to give them an advantage in future endeavors. Second, success often results in competitive advantages that increase with size, such as economies of scale and networking effects. So, once you start winning, the game gets much easier. The rich get richer.

But the rich getting richer is only half of the equation. I think it is also likely that the poor will get poorer.

Being unskilled sucks

Much of the work that people have done in the past is now being automated. Instead of weaving the fabric to make shirts, we have gigantic industrial looms that are far more productive than people. This is a good thing in general, since we get the goods we want at a cheaper cost. In effect, automation is magnifying the efforts of a few, so that a few people can potentially satisfy the needs of hundreds or thousands.

But this leads to a big problem. In our current economic system, automation should naturally widen the gulf between the rich and the poor. Those who control the means of production will create even more wealth. The poor, on the other hand, will no longer even be required as labor for goods production. If machines are doing all unskilled labor, the value of unskilled labor plummets, and the poor should become even poorer.

This hypothetical world isn’t great, even for the rich. The rich actually need the poor to purchase their widgets. If the poor can’t afford to buy the widgets, then the rich won’t be nearly as well off as they could be. Plus, if the divide between the rich and the poor becomes too large, it increases the chance that the poor will rise up, kill the rich, and take their stuff.

Are we there yet?

Some people are starting to argue that we’ve already passed the tipping point for automation. The recovery from the 2008 Great Recession has been the slowest ever. Historically, jobs lost during a recession come back within a couple years. With the Great Recession, it took over six years for the number of jobs in the USA to reach peak pre-recession levels.

There is speculation about why this recovery was so slow. This certainly wasn’t a typical recession. In 2008-2009, there was a real risk of the global banking system collapsing. The job losses were huge compared to previous recessions. That interest rates are still at “emergency” levels shows how worried the Federal Reserve continues to be. So, maybe the recovery is slow simply because the recession was huge.

Or, maybe the slow recovery is a side-effect of globalization, as large companies offshore anything that can be offshored. Labor costs are so much lower in other countries that perhaps we shouldn’t be surprised that companies are prioritizing hiring overseas to hiring in North America.

Or perhaps this is a consequence of automation. During the recession, companies had to become more efficient to keep their profits high. So perhaps they did that through automation–permanently eliminating jobs when a computer or robot could easily replace a human in a job.

My view

Which one of these three explanations is correct? I suspect all three, with the biggest factor being globalization. The combination of the Internet, structured Web Services, and improved logistics have made it more feasible than ever to outsource a production all over the globe.

In my personal experience working with large companies–and remember I have a tech background–I’ve seen the impact of automation and globalization. I’ve seen many cases where people were hired to talk to workers to determine how they do their job, so that they could make a computer do it instead and layoff the workers.

But I’ve also seen places where outsourcing wins. In one case, there was a highly-repetitive job involving searching structured data for anomalies–a task at which computers excel. A natural task to automate.

But in this case, the business decided to outsource the job. It was cheaper to hire Chinese workers to do this mind-numbingly boring work for years than it was to create and maintain an automated system.

The Chinese themselves make the same decisions. To a North American, many Chinese factories look primitive, not even using much of the basic automation that has been in place over here for decades. But for them, it’s often cheaper to hire people to do repetitive jobs than it is to purchase machinery with a high upfront cost that requires ongoing maintenance by a skilled technician.

The bottom line

So at this point, I think global labor arbitrage is a more significant factor in job losses than automation. Nevertheless, it seems clear that automation will be hugely important in the labor market going forward, and we could eventually reach the point where unskilled labor is essentially worthless. In my next blog entry, I’ll discuss one proposed solution to this problem, the minimum guaranteed income.